Even a “small crisis” could trigger a chain of events that would threaten the stability of the European Union, the credit ratings agency Moody’s has said. Brexit – if the UK votes to leave the 28-nation union – or even Grexit – the departure of Greece from the eurozone – are the obvious vulnerabilities.

But some commentators believe an altogether quieter crisis should also be at the top of the worry list: Italy’s battle to prop up its debt-laden banks.

The country that probably gave the English-speaking world the word for bank – medieval Italian merchants traded with each other on a bench known as banca – has a €360bn (£280bn) problem in its fragmented banking sector.

That sum is the amount of non-performing loans (NPLs) – loans on which customers’ repayments have fallen behind – being nursed by Italian banks. Eight years on from the start of the global financial crisis, when the UK’s banking meltdown was marked by the queues of panicking customers outside branches of the now defunct Northern Rock, Italy is facing decisions that “will shape not just the future of the Italian banking system but that of the European one as well”, according to analysts at the Hamburg-based bank Berenberg.

Banks across Europe have had a tough 2016. Shunned by investors, an index of shares for 600 European banks is down 22% so far. But Italy’s bank stock index is down 35%, with its biggest bank, Unicredit, having dropped 40%.

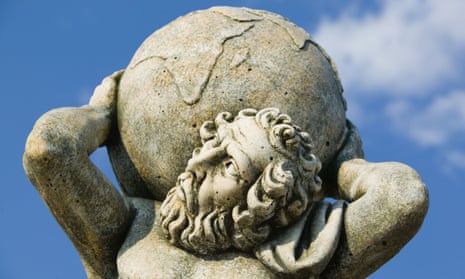

For inspiration, Matteo Renzi, the Italian prime minster, has turned to Greek mythology. A €4.25bn fund set up as a backstop for the banking sector derives its name, Atlante, from Atlas, the god condemned to hold up the sky.

The name alone indicates the herculean task it faces. Italy has more than 500 banks, and more branches than restaurants dotted across the eurozone’s third biggest economy. These heavy cost bases are hanging over them at a time when revenues are under intense pressure from the interest rate policy of the European Central Bank, which last month cut rates to zero.

The troubled loans amount to 18% of all lending, three times the EU average. Unlike the crisis which hit banks hard in Spain and Ireland, this situation has not arisen from a frenzy of lending to fuel a property boom before the 2008 bust, but through years of failing to tackle poor lending decisions worsened by a weak economy.

In waiting so long to tackle the matter, Italy has found it hard to copy Spain, which in 2012 created a “bad bank”, largely to house those troubled property loans. The EU has changed the rules on state aid since then.

“The Italian government has been severely constrained in its ability to emulate the Spanish example, due to high public debt and the new, more stringent EU state-aid rules, whereby NPL purchases by a public entity would trigger an onerous ‘bail-in’ of bank creditors,” said Federico Santi, an analyst at the risk consultancy Eurasia Group.

Those new EU rules require bondholders – and, crucially, savers – to take 8% of the liabilities before any government funds can be used to prop up banks in a bail-in, the aim of which is to prevent a bailout by taxpayers.

Forcing savers to take losses is unpalatable. Cyprus took that route three years ago, hitting savers with more than the €100,000 guaranteed by EU rules.

Just before Christmas, and before the EU rule change, Italy took steps to avoid depositors having to take losses in four lenders: Banca Etruria, Banca Marche, CariFerrara and CariChieti. But some bondholders were forced to take losses, sparking a furious reaction as the bonds issued by Italian banks are often bought by their retail customers. Renzi was accused of overseeing a “state suicide” when a retired man who lost €110,000 in Banca Etrutia bonds killed himself.

Renzi has adopted a three-pronged approach: the Atlante backup fund, which is also intended to be able to buy bad debts; a plan to allow banks to package up NPLs into bonds with a government guarantee to try to attract buyers – a sort of bad bank; and a move to speed up the time it takes to repossess properties, which can currently take up to 15 years.

Atlante’s first test came last week, when it was forced to shoulder a heavier burden than expected by taking control of Popolare di Vicenza, Italy’s eighth largest lender.

Vicenza’s €1.5bn fundraising was shunned by investors and Atlante’s involvement meant Unicredit was not forced to pick up the bill on its own.

Unicredit, which reported its results on Tuesday, had been expected to guarantee the cash call. “Had this fund not been in place, there would have been quite a tricky situation,” said Filippo Alloatti, a senior credit analyst at the fund manager Hermes. “The bank which had originally underwritten it, it would have had to consolidate Vicenza … or even worse, we would have had to have bail-in.”

Unicredit, which put €800m into Atlante, attempted to reassure investors as it reported better-than-expected results for the first quarter, pointing to an improvement in bad debt provisions in the period: €755m compared with €980m a year earlier.

The bank’s chief executive, Federico Ghizzoni, heralded a fifth consecutive quarter of falling bad debts. Ghizzoni, who, according to the Financial Times, is under pressure from shareholders, is also closing branches and cutting jobs, more than 3,000 of the latter have gone since last year.

On Tuesday he was upbeat, telling analysts: “I believe the government reforms … will altogether contribute to further improvement in the NPLs.”

One of the next tests is a €1bn cash call by Veneto Banca. This is being underwritten by a group of banks led by Intesa Sanpaolo. Veneto will begin testing investor appetite for its shares next week, according to reports, and its chairman, Pierluigi Bolla, will be hoping that Atlante is not required to act as a backstop.

The outcome will be scrutinised by bank bosses across Italy.